Story by Kate Julian

Updated at 10:30 a.m. ET on April 17, 2020.

Imagine for a moment that the future is going to be even more stressful than the present. Maybe we don’t need to imagine this. You probably believe it. According to a survey from the Pew Research Center last year, 60 percent of American adults think that three decades from now, the U.S. will be less powerful than it is today. Almost two-thirds say it will be even more divided politically. Fifty-nine percent think the environment will be degraded. Nearly three-quarters say that the gap between the haves and have-nots will be wider. A plurality expect the average family’s standard of living to have declined. Most of us, presumably, have recently become acutely aware of the danger of global plagues.

To hear more feature stories, get the Audm iPhone app.

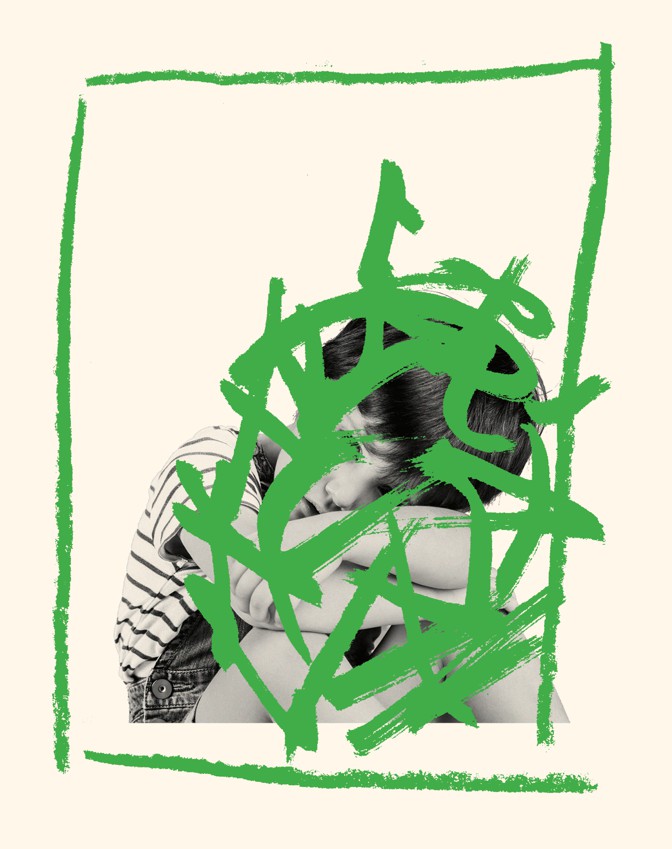

Suppose, too, that you are brave or crazy enough to have brought a child into this world, or rather this mess. If ever there were a moment for fortifying the psyche and girding the soul, surely this is it. But how do you prepare a child for life in an uncertain time—one far more psychologically taxing than the late-20th-century world into which you were born?

To protect children from physical harm, we buy car seats, we childproof, we teach them to swim, we hover. How, though, do you inoculate a child against future anguish? For that matter, what do you do if your child seems overwhelmed by life in the here and now?

You may already know that an increasing number of our kids are not all right. But to recap: After remaining more or less flat in the 1970s and ’80s, rates of adolescent depression declined slightly from the early ’90s through the mid-aughts. Shortly thereafter, though, they started climbing, and they haven’t stopped. Many studies, drawing on multiple data sources, confirm this; one of the more recent analyses, by Pew, shows that from 2007 to 2017, the percentage of 12-to-17-year-olds who had experienced a major depressive episode in the previous year shot up from 8 percent to 13 percent—meaning that, in the span of a decade, the number of severely depressed teenagers went from 2 million to 3.2 million. Among girls, the rate was even higher; in 2017, one in five reported experiencing major depression.

An even more wrenching manifestation of this trend can be seen in the suicide numbers. From 2007 to 2017, suicides among 10-to-24-year-olds rose 56 percent, overtaking homicide as the second leading cause of death in this age group (after accidents). The increase among preadolescents and younger teens is particularly startling. Suicides by children ages 5 to 11 have almost doubled in recent years. Children’s emergency-room visits for suicide attempts or suicidal ideation rose from 580,000 in 2007 to 1.1 million in 2015; 43 percent of those visits were by children younger than 11. Trying to understand why the sort of emotional distress that once started in adolescence now seems to be leaching into younger age groups, I called Laura Prager, a child psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a co-author of Suicide by Security Blanket, and Other Stories From the Child Psychiatry Emergency Service. Could she explain what was going on? “There are many theories, but I don’t understand it fully,” she replied. “I don’t know that anyone does.”

From December 2015: Hanna Rosin on the Silicon Valley suicides

One possible contributing factor is that, in 2004, the FDA put a warning on antidepressants, noting a possible association between antidepressant use and suicidal thinking in some young people. Prescriptions of antidepressants to children fell off sharply—leading experts to debate whether the warning resulted in more deaths than it prevented. The opioid epidemic also appears to be playing a role: One study suggests that a sixth of the increase in teen suicides can be linked to parental opioid addiction. Some experts have suggested that rising distress among preteen and adolescent girls might be linked to the fact that girls are getting their period earlier and earlier (a trend that has itself been linked to various factors, including obesity and chemical exposure).

Even taken together, though, these explanations don’t totally account for what’s going on. Nor can they account for the fragility that now seems to accompany so many kids out of adolescence and into their young-adult years. The closest thing to a unified theory of the case—one put forth in The Atlantic three years ago by the psychologist Jean M. Twenge and in many other places by many other people—is that smartphones and social media are to blame. But that can’t explain the distress we see in kids too young to have phones. And the more the relationship between phones and mental health is studied, the less straightforward it seems. For one thing, kids the world over have smartphones, but most other countries aren’t experiencing similar rises in suicides. For another, meta-analyses of recent research have found that the overall associations between screen time and adolescent well-being range from relatively small to nonexistent. (Some studies have even found positive effects: When adolescents text more in a given day, for example, they report feeling less depressed and anxious, probably because they feel greater social connection and support.)

A stronger case can be made that social media is potentially hazardous for people who are already at risk of anxiety and depression. “What we are seeing now,” writes Candice Odgers, a professor at UC Irvine who has reviewed the literature closely, “might be the emergence of a new kind of digital divide, in which differences in online experiences are amplifying risks among [the] already-vulnerable.” For instance, kids who are anxious are more likely than other kids to be bullied—and kids who are cyberbullied are much more likely to consider suicide. And for young people who are already struggling, online distractions can make retreating from offline life all too tempting, which can lead to deepening isolation and depression.

This more or less brings us back to where we started: Some of the kids aren’t all right, and certain aspects of contemporary American life are making them less all right, at younger and younger ages. But none of this suggests much in the way of solutions. Taking phones away from miserable kids seems like a bad idea; as long as that’s where much of teenagers’ social lives are transacted, you’ll only isolate them. Do we campaign to take away the happy kids’ phones too? Wage a war on early puberty? What?

Video: Kids Feel Pandemic Anxiety Too

Ihave been thinking about these questions a lot lately, for journalistic reasons as well as personal ones. I am the mother of two children, 6 and 10, whose lineage includes more than its share of mental illness. Having lost one family member to suicide and watched another ravaged by addiction and psychiatric disability, I have no deeper wish for my kids than that they not be similarly afflicted. And yet, given the apparent direction of our country and our world, not to mention the ordeal that is late-stage meritocracy, I haven’t been feeling optimistic about the conditions for future sanity—theirs, mine, or anyone’s.

From September 2019: Daniel Markovits on how meritocracy harms everyone

To my surprise, as I began interviewing experts in children’s mental health—clinicians, neuroscientists doing cutting-edge research, parents who’d achieved this unofficial status as a result of their kids’ difficulties—an unusually unified chorus emerged. For all the brain’s mysteries, for everything we still don’t know about genetics and epigenetics, the people I spoke with emphasized what we do know about when emotional disorders start and how we might head more of them off at the pass. The when: childhood—very often early childhood. The how: treatment of anxiety, which was repeatedly described as a gateway to other mental disorders, or, in one mother’s vivid phrasing, “the road to hell.”

Actually, the focus on anxiety wasn’t so surprising. Of course anxiety. Anxiety is, in 2020, ubiquitous, inescapable, an ambient condition. Over the course of this century, the percentage of outpatient doctors’ visits in America involving a prescription for an anti-anxiety medication such as Xanax or Valium has doubled.* As for the kids: A study published in 2018, the most recent effort at such a tabulation, found that in just five years, anxiety-disorder diagnoses among young people had increased 17 percent. Anxiety is the topic of pop music (Ariana Grande’s “Breathin,” Julia Michaels and Selena Gomez’s “Anxiety”), the country’s best-selling graphic novel (Raina Telgemeier’s Guts), and a whole cohort’s sense of humor (see Generation Z’s seemingly bottomless appetite for anxiety memes). The New York Times has even published a roundup of anxiety-themed books for little ones. “Anxiety is on the rise in all age groups,” it explained, “and toddlers are not immune.”

How do you inoculate a child against future anguish? What do you do if your child already seems overwhelmed in the here and now?

The good news is that new forms of treatment for children’s anxiety disorders are emerging—and, as we’ll see, that treatment can forestall a host of later problems. Even so, there is a problem with much of the anxiety about children’s anxiety, and it brings us closer to the heart of the matter. Anxiety disorders are well worth preventing, but anxiety itself is not something to be warded off. It is a universal and necessary response to stress and uncertainty. I heard repeatedly from therapists and researchers while reporting this piece that anxiety is uncomfortable but, as with most discomfort, we can learn to tolerate it.

Yet we are doing the opposite: Far too often, we insulate our children from distress and discomfort entirely. And children who don’t learn to cope with distress face a rough path to adulthood. A growing number of middle- and high-school students appear to be avoiding school due to anxiety or depression; some have stopped attending entirely. As a symptom of deteriorating mental health, experts say, “school refusal” is the equivalent of a four-alarm fire, both because it signals profound distress and because it can lead to so-called failure to launch—seen in the rising share of young adults who don’t work or attend school and who are dependent on their parents.

Lynn Lyons, a therapist and co-author of Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents, told me that the childhood mental-health crisis risks becoming self-perpetuating: “The worse that the numbers get about our kids’ mental health—the more anxiety, depression, and suicide increase—the more fearful parents become. The more fearful parents become, the more they continue to do the things that are inadvertently contributing to these problems.”

Read: What the coronavirus will do to kids

This is the essence of our moment. The problem with kids today is also a crisis of parenting today, which is itself growing worse as parental stress rises, for a variety of reasons. And so we have a vicious cycle in which adult stress leads to child stress, which leads to more adult stress, which leads to an epidemic of anxiety at all ages.

I. The Seeds of Anxiety

Over the past two or three decades, epidemiologists have conducted large, nationally representative studies screening children for psychiatric disorders, then following those children into adulthood. As a result, we now know that anxiety disorders are by far the most common psychiatric condition in children, and are far more common than we thought 20 or 30 years ago. We know they affect nearly a third of adolescents ages 13 to 18, and that their median age of onset is 11, although some anxiety disorders start much earlier (the median age for a phobia to start is 7).

Many cases of childhood anxiety go away on their own—and if you don’t have an anxiety disorder in childhood, you’re unlikely to develop one as an adult. Less happily, the cases that don’t resolve tend to get more severe and to lead to further problems—first additional anxiety disorders, then mood and substance-abuse disorders. “Age 4 might be specific phobia. Age 7 is going to be separation anxiety plus the specific phobia,” says Anne Marie Albano, the director of the Columbia University Clinic for Anxiety and Related Disorders. “Age 12 is going to be separation anxiety, social anxiety, and the specific phobia. Anxiety picks its own friends up first before it branches into the other disorders.” And the earlier it starts, the more likely depression is to follow.

All of which means we can no longer assume that childhood distress is a phase to be grown out of. “The group of kids whose problems don’t go away account for most adults who have problems,” says the National Institute of Mental Health’s Daniel Pine, a leading authority on how anxiety develops in children. “People go on to develop a whole host of other problems that aren’t anxiety.” Ronald C. Kessler, a professor of health-care policy at Harvard, once made this point especially vividly: “Fear of dogs at age 5 or 10 is important not because fear of dogs impairs the quality of your life,” he said. “Fear of dogs is important because it makes you four times more likely to end up a 25-year-old, depressed, high-school-dropout single mother who is drug-dependent.”

Compounding this, the young kids with mental-health problems today may have worse long-term prospects than did similar kids in decades past. That is the conclusion drawn by Ruth Sellers, a University of Sussex research psychologist who examined three longitudinal studies of British youth. Sellers found that youth with mental-health problems at age 7 are more likely to be socially isolated and victimized by peers later in childhood, and to have mental-health and academic difficulties at age 16. Concerningly, despite decreased stigma and increases in mental-health-care spending, these associations have been growing stronger over time.

Big societal shifts such as the ones we’ve undergone in recent years can hit people with particular traits particularly hard. A recent example comes from China, where shy, quiet children used to be well liked and tended to thrive. Following rapid social and economic change in urban areas, values have changed, and these children now tend to be rejected by their peers—and, surely no coincidence, are more prone to depressive symptoms. I thought of this when I met recently with the leaders of a support group for parents of struggling young adults in the Washington, D.C., area, most of whom still live at home. Some of these grown children have psychiatric diagnoses; all have had difficulty with the hurdles and humiliations of life in a deeply competitive culture, one with a narrowing definition of success and a rising cost of living.

The hope of early treatment is that by getting to a child when she’s 7, we may be able to stop or at least slow the distressing trajectory charted by Sellers and other researchers. And cognitive behavioral therapy, the most empirically supported therapy for anxiety, is often sufficient to do just that. In the case of anxiety, CBT typically involves a combination of what’s known as “cognitive restructuring”—learning to spot maladaptive beliefs and challenge them—and exposure to the very things that cause you anxiety. The goal of exposure is to desensitize you to these things and also to give you practice riding out your anxious feelings, rather than avoiding them.

Most of the time, according to the largest and most authoritative study to date, CBT works: After a 12-week course, 60 percent of children with anxiety disorders were “very much improved” or “much improved.” But it isn’t a permanent cure—its results tend to fade over time, and people whose anxiety resurges may need follow-up courses.

Illustration: Oliver Munday; Marco Pasqualini / Getty

Illustration: Oliver Munday; Marco Pasqualini / Getty

A bigger problem is that cognitive behavioral therapy can only work if the patient is motivated, and many anxious children have approximately zero interest in battling their fears. And CBT focuses on the child’s role in his or her anxiety disorder, while neglecting the parents’ responses to that anxiety. (Even when a parent participates in the therapy, the emphasis typically remains on what the child, not the parent, is doing.)

A highly promising new treatment out of Yale University’s Child Study Center called SPACE (Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions) takes a different approach. SPACE treats kids without directly treating kids, and by instead treating their parents. It is as effective as CBT, according to a widely noted study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry earlier this year, and reaches even those kids who refuse help. Not surprisingly, it has provoked a tremendous amount of excitement in the children’s-mental-health world—so much so that when I began reporting this piece, I quickly lost track of the number of people who asked whether I’d read about it yet, or talked with Eli Lebowitz, the psychology professor who created it.

In working directly with parents, Lebowitz’s approach aims to provide not a temporary solution, but a foundation for a lifetime of successful coping. SPACE is also, I have come to believe, much more than a way of treating childhood anxiety—it is an important keyhole to the broken way American adults now approach parenting.

When lebowitz teaches other clinicians how to do SPACE, he starts by telling them, several times, that he’s not blaming parents for their kids’ pathologies.

“Because we represent a field with a very rich history of blaming parents for pretty much everything—autism, schizophrenia, eating disorders—this is a really important point,” he said one Sunday morning in January, as he and his collaborator Yaara Shimshoni kicked off a two-day training for therapists. A few dozen were in attendance, having traveled to Yale from across the country so that they might learn to help parents reduce what Lebowitz calls “accommodating” behaviors and what the rest of us may call “behaviors typical of a 21st-century parent.”

“There really isn’t evidence to demonstrate that parents cause children’s anxiety disorders in the vast majority of cases,” Lebowitz said. But—and this is a big but—there is research establishing a correlation between children’s anxiety and parents’ behavior. SPACE, he continued, is predicated on the simple idea that you can combat a kid’s anxiety disorder by reducing parental accommodation—basically, those things a parent does to alleviate a child’s anxious feelings. If a child is afraid of dogs, an accommodation might be walking her across the street so as to avoid one. If a child is scared of the dark, it might be letting him sleep in your bed.

Lebowitz borrowed the concept about a decade ago from the literature on how obsessive-compulsive disorder affects a patient’s family members and vice versa. (As he put it to me, family members end up living as though they, too, have OCD: “Everybody’s washing their hands. Everybody’s changing their clothes. Nobody’s saying this word or that word.”) In the years since, accommodation has become a focus of anxiety research. We now know that about 95 percent of parents of anxious children engage in accommodation. We also know that higher degrees of accommodation are associated with more severe anxiety symptoms, more severe impairment, and worse treatment outcomes. These findings have potential implications even for children who are not (yet) clinically anxious: The everyday efforts we make to prevent kids’ distress—minimizing things that worry them or scare them, assisting with difficult tasks rather than letting them struggle—may not help them manage it in the long term. When my daughter is in tears because she hasn’t finished a school project that’s due the next morning, I sometimes stop her crying by coaching her through the rest of it. But when I do, she doesn’t learn to handle deadline jitters. When she asks me whether anyone in our family will die of COVID-19, an unequivocal “No, don’t worry” may reassure her now, but a longer, harder conversation about life’s uncertainties might do more to help her in the future.

Despite more than a decade’s evidence that helicopter parenting is counterproductive, kids today are perhaps more overprotected, more leery of adulthood, more in need of therapy.

Parents know they aren’t helping their kids by accommodating their fears; they tell Lebowitz as much. But they also say they don’t know how to stop. They fear that day-to-day life will become unmanageable.

Posted on April 18, 2020

0